Access to Information, The Media Trust, and Duke University: September Update

Ransomware has become a top cybersecurity risk in recent years and it shows no signs of slowing down. Yet ask the average person to conjure an image of how a breach occurs and they are likely to paint a picture more similar to The Matrix than reality. This description of how the attacks happen is engaging, but vastly overestimates the complexity of implementing a ransomware attack. Gaining access to a target’s system can be done quickly and easily through a vulnerability present nearly everywhere, third-party code. This third-party code creates the potential for Backdoors as a Service, which greatly raises the risk of a far-reaching marketplace for ransomware and other cybersecurity attacks.

Third-party code is code delivered to a website by an outside domain not operated by the owner of said website. This may seem surprising, but according to research done by The Media Trust, an internet security company, this code makes up 65 to 95 percent of the average website and is responsible for nearly all online advertising. This is not inherently a bad thing. Organizations rely on third-party code for a variety of vital functions such as advertising, payment processing, and analytics. Designing all of these tools in-house would require a massive investment and in some cases be nearly impossible. The functionality and simplicity of third-party code has the result of making it ubiquitous across the web. However, the convenience of this code is offset by the security vulnerabilities it brings that allow criminals to perpetrate a wide variety of attacks.

No matter how strong a site’s security is in the first-party code it delivers, third-party code creates the opportunity for backdoors that malicious actors can exploit. The vast majority of websites fail to account for the risks present in code that is not created internally, and if these are exploited a wide range of dangerous consequences become possible. Currently, the top risk from third-party code is ransomware, but other types of attacks also create substantial dangers for end-users and the organizations that provide them with devices and internet access. Cryptojacking, DDoS Bots, Banking Trojans, and Cross-Site Request Forgery are just some of the other destructive capabilities criminals gain when they find a backdoor. These attacks are not new, but their prevalence in third-party code poses an unprecedented level of threat.

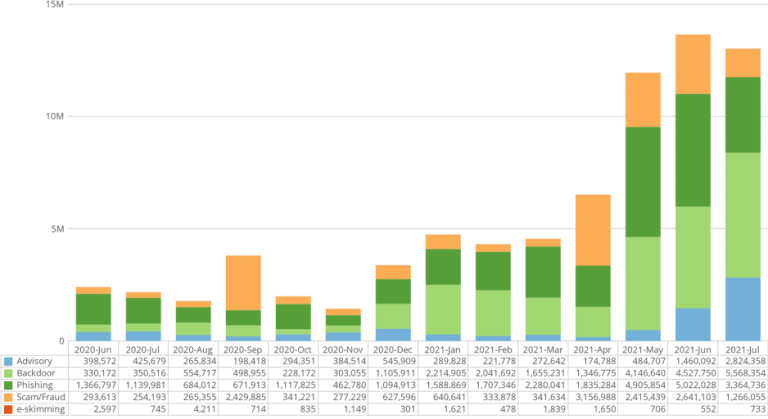

Our research team has been analyzing data obtained from The Media Trust which has shown a significant increase of malicious activity over the past three months detected from these sources. In May, June, and July approximately 12 million, 13.6 million, and 13 million instances of malware in third-party code have been detected. This represents nearly 2 percent of the almost 900 million total scans The Media Trust does monthly. Thus 1 in 50 webpages on the internet have a security vulnerability arising from third-party code, a frequency that threatens every individual and organization that access the web. These incidents include phishing attacks, scams, advisory, e-skimming, and the aforementioned backdoors. Backdoors, which make up 37 percent of these attacks, are particularly concerning as once a malicious organization has access to a machine, they can then execute other cybersecurity attacks such as ransomware or the theft of intellectual property.

The primary vector for these attacks is the online advertising industry where third-party code is ubiquitous. The privacy violations and dangers from online advertising have been well documented. National security, racial discrimination, and disinformation are some of the many threats arising from online advertising’s collection and use of data about the individual visitors of websites. On its own the use of personal data profiles necessitates governmental regulation to prevent these risks, but privacy is not the only consequence of advertising. Third-party code from online ads opens up both websites and users to security vulnerabilities. Privacy and security are often seen as competing in a zero-sum game, but in this instance they are both threatened by online advertising’s delivery of third-party code.

Ads are not the only point of access for third-party code, just the most common. Other plug-ins and software can similarly target both users and systems. Further, the ease of access from this code allows bad actors to tailor their attacks to specific goals. This primarily takes two forms. One method is to cast a wide net and mass-compromise as many users as possible going for a quantity over quality approach. The other is to target specific high value victims to get the greatest benefit from a single attack. This could take the form of picking out critical infrastructure that can’t stay offline for long such as with the recent Colonial Pipeline attack, or it could mean focusing on rich targets who are likely to pay a large ransom. Third-party code also opens the door for the growing field of Ransomware as a Service (RaaS), the model used in the Colonial Pipeline attack. RaaS operators offer ransomware products for sale giving even those without technical expertise the ability to lead a major attack. However, third-party code is giving this industry the capability to expand into a far more dangerous and versatile area. Namely, they can begin offering “backdoors as a service”.

Selling backdoors is not a new phenomenon. Primarily using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) cybercriminals are able to sell access to networks to the highest bidder without anyone even knowing they were compromised. Nonetheless the security vulnerabilities of RDP are well known and avoidable. In contrast, there is a low level of understanding surrounding third-party code and malicious actors can exploit it to open up backdoors at an unprecedented scale. With the vast amount of networks third-party code opens up to breach, the possibility of backdoor selling becoming a common service is a far greater possibility.

Backdoors as a service represent a significant national security threat to the United States. Ransomware has mostly been limited in its aims with monetary compensation the primary goal. The criminals behind these actions have generally not sought to harm users or degrade critical infrastructure. This is why many ransomware groups have begun establishing a reputation as easy to negotiate with and reliable to ensure their victims pay their ransoms. Selling backdoors on the other hand gives the buyers the capability to cause much more damage. There are a variety of actors such as terrorists and intelligence agencies who will happily exploit backdoors as a service, and with recent breaches like Solarwinds attributed to foreign nation-states cyberattacks are becoming inextricably linked to geo-politics. Countries are increasingly turning to cyberspace to pursue their aims and third-party code is making this easier than ever. If the growth in backdoors truly leads to a marketplace for these exploits entities that wish the U.S. harm can easily compromise critical infrastructure and sensitive information from government systems. As this rapid growth in malware from third-party code continues backdoors as a service become a much more viable and impactful threat.

Much of the U.S. critical infrastructure is owned and operated by private companies. Data breach and privacy laws remain fractured and inconsistent offering no easy standard for coordination. Further, reports by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs have consistently found that government agencies’ cybersecurity measures require significant improvement. These lapses include a failure to protect personally identifiable information or install security patches introducing a variety of security risks that threaten their operation. This leaves all of these organizations and governmental entities dangerously exposed to the risk of third-party code and backdoors. If this is left unchecked the possibility of backdoors as a service will increase and threaten to substantially undermine national security.

Source: http://www.triangleprivacyhub.org/access-to-information-the-media-trust-and-duke-university-september-update/